The committee in Solidary with the People of El Salvador originally published the following article on the CISPES website on August 2, 2024.

To help paint the image of a successful war on gangs, in recent years Salvadoran president Nayib Bukele has promoted a narrative that his security policies are resulting in fewer people are leaving the country. Recently, this narrative has gotten a boost in the U.S., from MAGA proponents to mainstream press. Soon after his June 1 inauguration for an illegal second term, to which U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro led a sizable delegation from the Biden administration, the Associated Press ran a piece arguing that the U.S. is now supporting Bukele because migration numbers from El Salvador are going down, and the numbers are going down because Bukele’s approach is “working.” This framework, however, ignores other explanations for the Biden administration’s increasing demonstrations of support for Bukele, and does not align with a lot of data about continued migration out of El Salvador today, which tells a much more complex story.

The Salvadoran Embassy in the U.S. insists that Bukele has created the conditions for Salvadorans abroad to return to the country and that most are eager to do so, even pushing a new hashtag, #MigracionInversa (inverse migration). However, experts have countered that while the data, unsurprisingly, show that most Salvadorans who’ve had to leave the country want to return someday, less than 20% have concrete plans to do so.

This narrative has also jeopardized and sidelined the demands of nearly 200,000 Salvadorans counting on the renewal of Temporary Protected Status, and hundreds of thousands more who are fighting to remain in the U.S., especially given the increasing danger of being deported to Bukele’s police state. Prominent immigrant rights organizations have been calling for the redesignation of TPS for all Salvadorans, not just an extension for current TPS holders who arrived prior to February and March of 2001. These calls have been echoed by over one hundred U.S. lawmakers, who point to the human rights crisis under Bukele’s State of Exception as a primary reason that Salvadorans in the United States cannot return to the country.

Certainly, Bukele’s promise that he will decrease the number of Salvadorans in the United States appeals to many white nationalists who have flocked to Trump for his outright racism and xenophobia. In fact, a high-profile MAGA delegation also joined Bukele’s inauguration, including Don Trump, Jr., Tucker Carlson and Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL), who has since returned again to marvel at Bukele’s repressive state apparatus, including the largest prison in the hemisphere.

That’s why many were shocked that former president Trump recently appeared to throw Bukele under the bus during his July 18th speech at the Republican National Convention, stating that Bukele had only reduced the homicide rate by sending those who had been committing murders to the U.S. The aim, of course, was to rile up his base before promising the largest deportation raids in the history of the United States. But the Bukele administration has played into this dangerous narrative, too. After all, according to their logic, if El Salvador is now a paradise, only criminals attempting to avoid imprisonment in his mega-prison, the Center for Terrorist Containment (CECOT), have reason to leave.

The end result is that Salvadoran migrants continue to be painted as criminals, now even by their own government. This masks the real reasons why many Salvadorans are continuing to flee the country, including the worsening political repression, human rights, and economic conditions he has created, and leaves human rights and migration experts in El Salvador to fight an uphill battle to paint the true picture of migration from the country today.

Recounting the numbers

Many in Washington seem to be pointing to a specific statistic from Customs and Border Patrol in order to justify Bukele’s alleged “tough-on-crime” approach as successful. In FY2023, CBP Southwest border encounters of Salvadorans totalled 61,515, a decrease from the FY2022 total of 97,030. However, CBP border encounters alone do not paint a comprehensive picture of Salvadoran migration, nor is a one-year drop a clear or permanent indicator of decreasing emigration from or improving living conditions in El Salvador.

Examining the total number of encounters at the U.S.’ southwest border during Bukele’s first term utilizing CBP data from FY2020-FY2024 (through June 2024) reveals a total of 319,143 encounters. Meanwhile, between FY2015-FY2019, encompassing the previous presidential term of the FMLN’s Sánchez Cerén, the total number of encounters stood at 286,352. (See compilation of yearly data here). This amounts to an overall 11.5% increase over the previous five-year period, even despite universally lower numbers of human mobility in 2020 due to the COVID pandemic and the fact that U.S. border policies have been increasingly externalized onto Mexico in the past five years, as discussed in the following section.

Data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) can provide more comprehensive statistics on Salvadoran displacement. According to UNHCR Refugee Data Finder, which compiles the number of refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced persons, and other persons of concern, the number of displaced Salvadorans assisted by UNHCR in 2023 totalled 405,464, up from 332,383 in 2022 and 250,619 in 2018. The increase of asylum seekers and refugees in the last year signals rising persecution and the Salvadoran government’s failure to protect its citizens.

The data provided by UNHCR also demonstrates a decreasing number of Salvadorans being granted refugee status in the U.S. in the past five years. In 2023, the U.S. only received 51% of all Salvadoran refugees worldwide, compared to the 62% in 2018, meaning that the U.S. has taken less responsibility in providing protections for displaced Salvadorans.

Mexico’s role in migration to the U.S.

Mexico also plays a critical role in Salvadoran migration. Especially since the launch of Mexico’s Southern Border Plan in 2014, the U.S. has increasingly pressured Mexico to prevent migrants and refugees from reaching the U.S.-Mexico border. As a result, Mexico has heightened militarization and securitization measures, including at its own southern border with Guatemala and throughout its national territory. Additional externalization policies designed to delay or prevent migrants’ entry into the U.S. were implemented under Trump’s administration and many continued under Biden. For instance, Title 42, enacted by Trump in 2020 purportedly to curb the spread of COVID-19, remained in effect until May 2023.

Salvadorans now face an increasingly difficult journey through Mexico, often remaining there for longer than anticipated, or tragically, not surviving the harsh conditions imposed by Mexican immigration officials. The fire at the Ciudad Juarez migrant detention center, resulting in the deaths of 40 detainees, including 12 Salvadorans, highlights the severe conditions migrants face due to Mexico’s increased securitization.

Despite the harsh realities, data suggest that Salvadoran migration through Mexico continues to increase. In the first half of 2024, Mexico’s refugee processing agency Comision Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR) has cited a 10.41% increase in refugee applications from Salvadoran nationals compared to 2023, while applications from the other top ten countries of applicants decreased. While various factors could be contributing to this increase in numbers, it indicates that the number of Salvadoran refugees in Mexico is increasing. Additionally, data from Mexico’s Immigration Policy Unit indicates a significant rise in encounters with Salvadorans in irregular migration status. In 2023, Mexican officials documented 24,182 encounters with undocumented Salvadoran migrations. Between January and May of 2024 alone, that number had already risen to 33,292.

So, if conditions are so safe in El Salvador, then why are people still leaving at high rates?

Political persecution and repression

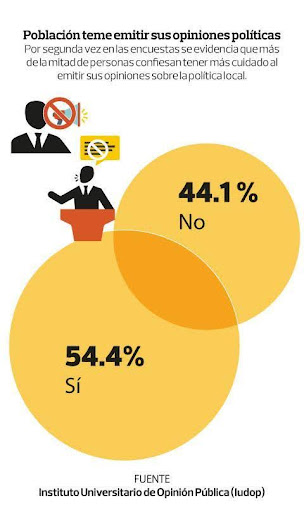

Bukele’s seemingly high approval rates are shadowed by increasing political repression. In a survey conducted by the University of Central America’s Institute of Public Opinion (Iudop) published in May of this year, 54.4% of the respondents claimed they were cautious about expressing their political opinions, the second time during Bukele’s presidency that over half of the surveyed population has reported feeling fearful about expressing political opinions publicly.

This is hardly unexpected given political persecution against political opponents, community leaders, and journalists as well as the arbitrary nature of so many of the arrests under Bukele’s ongoing State of Exception. After constitutional rights were suspended in March of 2022, many communities have been militarized and approximately 80,000 people have been swept up without warrants and unjustly detained, the vast majority solely on allegations of “illicit association.” Human rights organizations in El Salvador estimate that at least 26,000 of those who have been detained have no criminal involvement at all, but nearly all who have been arrested are from poor neighborhoods. The latest reports indicate that over 3,000 children have been arrested and tortured in prison and that at least 261 people have died. As prominent El Salvador-based human rights organization CRISTOSAL wrote in 2023, “the systematic perpetration of these violations of human rights as state policy coming from the highest level, systematic in nature and directed at a specific segment of the population (people residing in high-conflict areas, poor, and majority youth), allows for them to be classified as crimes against humanity (article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court).”

Following this complete disregard for due process, Bukele’s administration has targeted environmental defenders, former FMLN members and opposition leaders, and human rights defenders for arrest, reflecting a clear strategy to silence dissent. However, politically motivated arrests did not begin with the State of Exception in March of 2022. In a publication released prior to the implementation of the State of Exception, there were already over 50 documented instances of Salvadorans fleeing the country due to political persecution by the Bukele administration. Thus, the current State of Exception represents an escalation of the repressive politics that Bukele has implemented since taking office in 2019.

Internal displacement

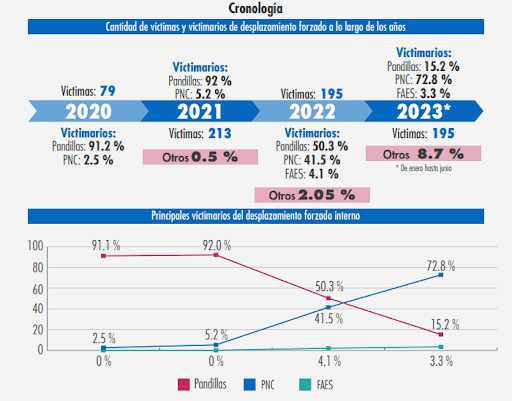

State violence, including threats, misconduct, and retaliation by police and military are also forcing Salvadorans to leave their homes and communities, even if they remain in the country. According to a 2023 report on internal displacement within El Salvador, CRISTOSAL, the Human Rights Institute of the University of Central America (IDHUCA), and Servicio Social Pasionista found that, since 2022, the year the State of Exception came into effect, police and military have replaced gangs as the main drivers of internal displacement (see below).

In 2020 and 2021, gangs made up 91.2% and 92% of the perpetrators of internal displacement in the cases received by these organizations, respectively. By 2023, the National Civil Police accounted for 72.8% of the perpetrators in cases of internal displacement and the Armed Forces an additional 3.3%. In just the first half of 2023, the number of victims (195) already equaled the total for the prior year and was set to far outpace the number of victims in 2021 (213), when gangs were reported as the main perpetrators of violence.

Declining economic conditions

For those Salvadorans who remain in the country, the worsening economic conditions cannot be ignored. During his illegal inauguration for a second term, Bukele vowed, once again, to provide “bitter medicine” to the country to revive the economy.

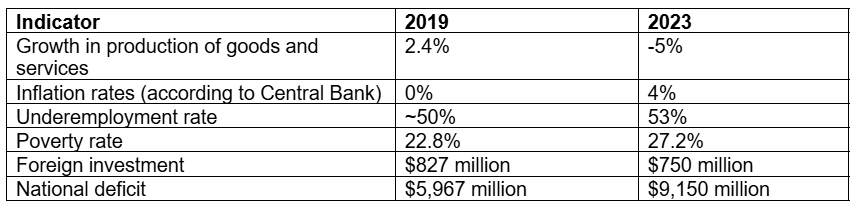

Popular education collective Equipo Maíz recounts various indicators of a deteriorating economy following Bukele’s first term (see below). Production rates have decreased while inflation rates have increased along with poverty and underemployment rates. Furthermore, the cost of living has increased by 28% in urban areas and 23% in rural areas, reaching levels that are unaffordable for many. In a recent survey by the University of Francisco Gavidia, Salvadorans cited the economy as a major concern, with 50% mentioning that they felt a significant increase in the cost of living in the past year.

So far, the government’s “bitter medicine” has meant cuts in gas subsidies, healthcare, education, and water services. Furthermore, Bukele has promised to eliminate tariffs for the next 10 years on imports as a supposed solution to the rising costs of basic goods, something that had already been implemented in 2022. As the Bloque de Resistencia y Rebeldía Popular points out, not only did this not improve the cost of goods, but it created long-lasting negative effects on national production rates.

The false promises made by Bukele continue to benefit the few while taking the largest toll on El Salvador’s poorest families, inevitably forcing many to migrate. Economic conditions have been the main drivers of migration out of El Salvador in the post-war period. However, the percentage of people leaving due to economic factors is on the rise. According to data from the International Organization of Migration, between January and April 2022, 64.1% of adults who had left El Salvador said it was due to economic conditions. Between January and June 2024, that percentage had risen to 73.5% of adults between January and June 2024.

The ongoing struggle

A look beyond just short-term trends at the U.S.-Mexico border makes clear that large numbers of Salvadorans continue to migrate. The underlying issues driving displacement of Salvadorans remain unresolved as economic conditions continue to affect more and more families, and political repression and persecution rise. Trump’s – and Bukele’s – portrayal of Salvadoran migrants as dangerous gang members not only stigmatizes and endangers an entire population but also serves as a smokescreen for the crises facing many working-class families in El Salvador under the current dictatorial regime.

The theory that the Biden administration’s ongoing support for Bukele is based on a reduction in migration, whether the numbers bear that out or not, also perpetuates the myth that U.S. foreign policy is genuinely interested in addressing the root causes of migration and allowing living conditions in Central America to improve. In reality, U.S. foreign policy stances, including continued support for Bukele, are more often than not driven by economic and geopolitical interests, like competition with China, and result in continued displacement from countries like El Salvador. It also upholds the dangerous policies of migrant containment that the anti-immigrant political discourse in the U.S. fuels, and on which Bukele’s government has proven eager to collaborate.

El Tribuno del Pueblo brings you articles written by individuals or organizations, along with our own reporting. Bylined articles reflect the views of the authors. Unsigned articles reflect the views of the editorial board. Please credit the source when sharing: tribunodelpueblo.org. We’re all volunteers, no paid staff. Please donate at http://tribunodelpueblo.org to keep bringing you the voices of the movement because no human being is illegal.